(It should take about four minutes to read this 684-word essay. There are links to sources at the end. Thank you for spending time with Snack.)

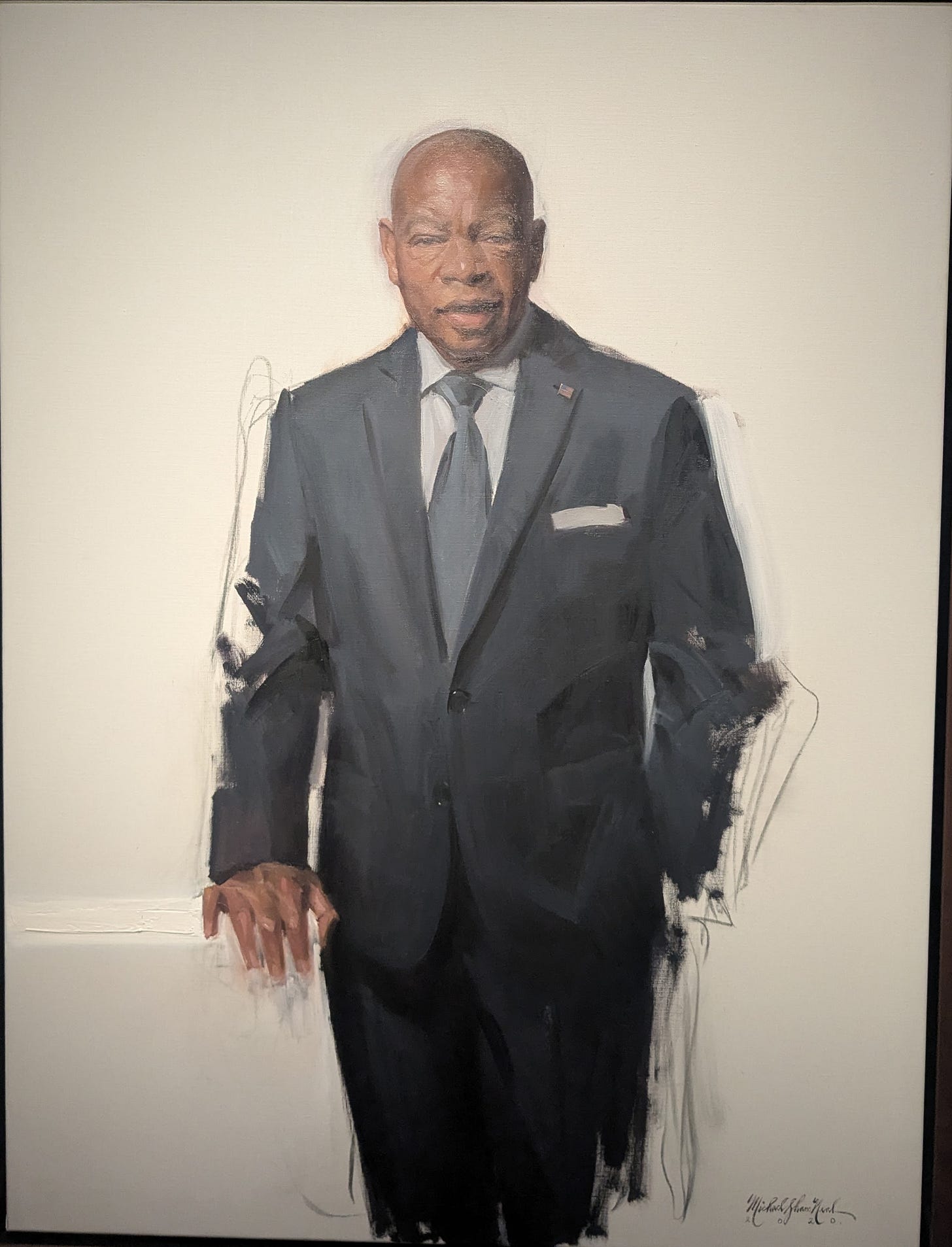

I stop in often to visit with the late Rep. John Lewis (1940-2020), known best for his "good trouble” approach to addressing injustice.

When I go to the National Portrait Gallery, I usually spend a few minutes with the painting of Lewis shown above.

There’s a lot to see at the National Portrait Gallery, which shares a home in downtown D.C. with the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Each museum has an impressive permanent collection. Both continually host thoughtful temporary exhibitions.

Their shared Greek Revival-style building would be a worth a look even if it were empty. Originally constructed for the Patent Office, this building was meant to be a “temple to the industrial arts.”

A roof made of waving glass and steel shelters the building’s large central courtyard. With tall trees and well-tended plants, the courtyard is a wonderful garden spot, especially on chilly days.

I tell you all of this to explain why I’m often at this museum complex.

So why visit over and over with the portrait of Lewis when I go there?

For inspiration.

If you know only a little about Lewis, you likely know he was a longtime advocate for civil rights.

As a young man, Lewis embraced the concept of nonviolence. He had the discipline to stick with it even when he was attacked, as happened in 1965 in Selma, Alabama.

Lewis kept trying until his last days to make the United States more just, to help it try to live up to its potential.

Everything I’ve read by or about Lewis tells me he was kind but dogged, that he was enlightened and stubborn. His relentless optimism shines through.

“Be like a pilot light and burn and burn and burn”

There’s a message in the painting of Lewis at the National Portrait Gallery that might not be obvious.

In a post on the website of the firm Portraits Inc., the artist Michael Shane Neal explains why his painting of Lewis differs from some of his other work:

"I left the edges ‘unfinished’ where the charcoal is still visible to express the unfinished nature of his work,” Neal says.

Lewis died in 2020. The New York Times ran a few days after his death an op-ed he’d prepared ahead of time. It encouraged us to carry on with his cause.

In the op-ed, Lewis recalled the effect on him as a young man in rural Alabama of hearing Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. speaking on the radio. That was his introduction to King’s philosophy and discipline of nonviolence. It set a direction Lewis would follow the rest of his life.

“Though I may not be here with you, I urge you to answer the highest calling of your heart and stand up for what you truly believe. In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace, the way of love and nonviolence is the more excellent way. Now it is your turn to let freedom ring,” Lewis wrote.

During his life, Lewis gave people practical tips as well as lofty goals. He frequently explained that the battle for justice is a long one. It requires persistence and perseverance.

“You have to pace yourself. You cannot be like a firecracker, just pop off,” Lewis said at a 2013 event. “You have to be like a pilot light and burn and burn and burn.”

Sources:

Portraits Inc. blog, Neal Portrait of Congressman John Lewis Acquired by Smithsonian | Lewis, Together, You Can Redeem the Soul of Our Nation, NYT, July 2020 | C-SPAN clip of Lewis speaking at the National Archives, 2013

For more on Lewis, including his advocacy for same-sex marriage, read my essay on Medium